Why choose this topic?

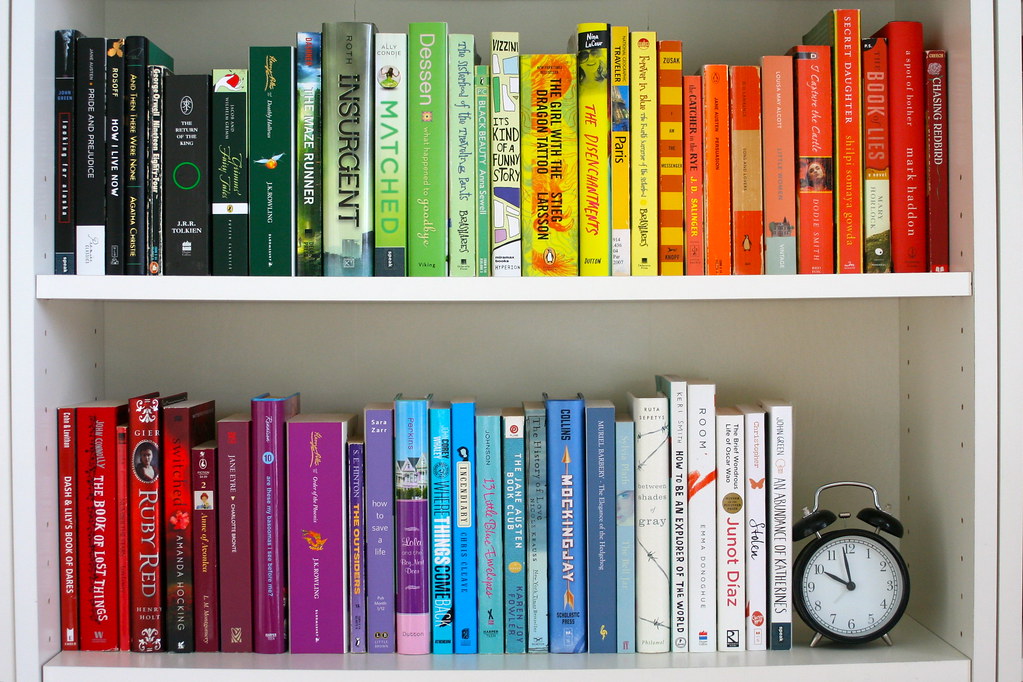

I have chosen to write about young adult literature specifically because it is an important lens through which to examine cultural shifts, as a microcosm for our society. Because YA books are geared toward new generations, what is changing in YA reflects what is changing in our world — and the treatment of queer people is no exception.

However, first and foremost, I chose this topic because I am passionate about it. I believe that positive queer representation for young people is incredibly important. Teens are in a state of transition, constantly evolving and searching for their sense of self, and if young queer people are unable to hear the stories of people like them in the literature they tend to consume, it makes it more difficult for them to understand and develop a sense of identity, leading to feelings of isolation and wrongness. Harmful queer representation can do an equal, if not larger, amount of damage. It is also important to ensure that young straight people are reading about those unlike themselves in order to learn and grow- education and exposure is always the key to enlightenment and tolerance.

There are, perhaps, those who believe that it is inappropriate to expose young people to LGBTQ+ characters, which may stem from the sexualisation of many facets of the queer experience in our society today, which I’ll get into a bit later. In response to those people, I would quote Rebecca Sugar, a prominent bisexual creator of children’s media, who states that “If you wait to tell queer youth that it matters how they feel or that they are even a person, then it’s going to be too late.”

Historical context

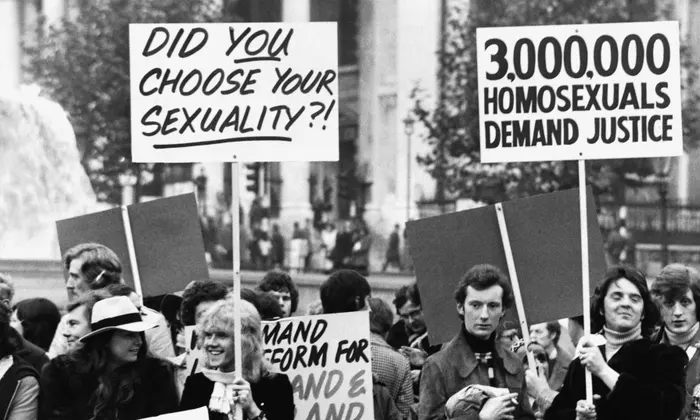

The rise of YA literature has, interestingly, mirrored the rise of LGBTQ+ activism in society. Both began to become more prominent in the middle of the 20th century. After World War two, adolescence began to be defined as a unique life stage, and the idea of the teenager emerged. This was primarily due to the postwar economic boom of the 1950s-70s and the sexual revolution of the 60s.

Living standards were rising with high employment rates, and parents were having fewer children due to both the rise of female education and introduction of the birth control pill (1961). This meant that teenagers had more disposable income and became an incredibly popular commercial market audience, especially in the literary industry.

The aforementioned sexual revolution of the 1960s also had a huge effect on queer activism. The increased regard for human rights and autonomy of the individual had a large impact on people’s attitudes and led to the occurrence of many important events. Trans people of colour in particular played pioneering roles in protests such as the Compton’s cafeteria riot in 1966 and the Stonewall riots in 1969. There was also a wave of decriminalisation in the late 20th century, taking place in England and Wales in 1967. It is important to note that female homosexuality had never actually been illegal in the UK, and that this 1967 act only referred to male homosexual acts.

Therefore, due to a combination of these social circumstances, the very first queer YA novel was released in 1969, just before the Stonewall riots. John Donovan’s ‘I’ll get there. It better be worth the trip.’ follows 13 year old Davy, who kisses and has a sexual encounter with another boy in his school. After this, his dog gets killed in a hit and run, and he wonders whether his homosexual acts were the cause, though maintaining that he isn’t ashamed of them. Perhaps the book needed to end in this ambiguity to be published- homophobes and queer people alike were able to read it as confirming their contradictory views.

Queer tragedy tropes

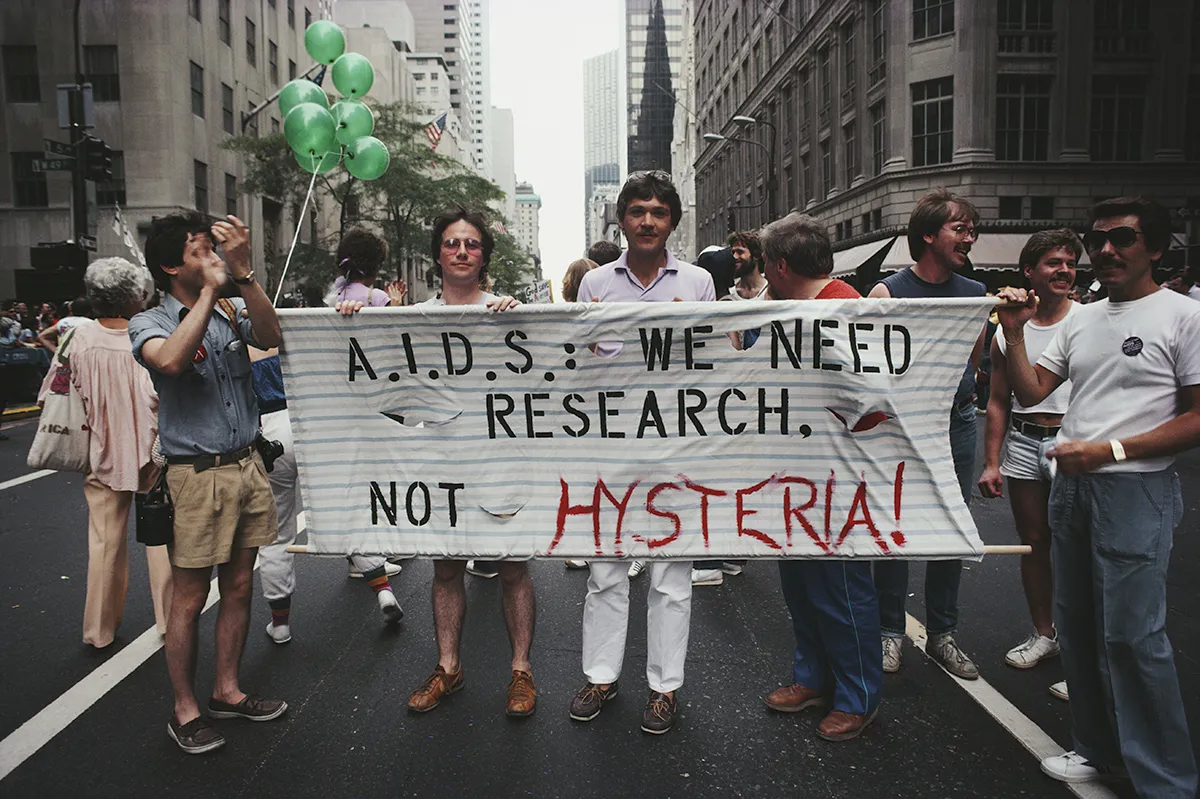

In this book, we come across a lot of tragedy. In fact, in all three of the novels following ‘I’ll get there’ in the queer YA genre, the queer character or their close friend dies. Unfortunately, filling a queer character’s journey with tremendous amounts of pain and suffering is still a feature of many pieces of YA literature today. This is troubling, as it can cause young queer people to grow accustomed to associating their own queer experience with pain, and a loss and lack of joy. This is a very complicated concept, of course, as a lot of queer history is rife with pain and suffering, so attempting to understand one’s queerness through the lens of oppression is entirely valid. Events like the HIV/AIDS crisis and horrifying ordeals such as conversion therapy should indeed by addressed in YA fiction and cannot be depicted in a positive light. However, as we see the world around us changing for the better, queer literature is still so often only diffused through grief that it’s impossible not to acknowledge the fact that this must, at least partly, be due to homophobic and transphobic rhetoric. Is a happy ending where a queer person is allowed to live out their life in peace simply less compelling to a straight audience?

It may be argued that sometimes, gay characters die in fiction because, sometimes, people die. LGBTQ+ readers cannot expect immunity for queer characters. This is true, of course- however, when queer characters are disproportionately underrepresented in media, killing off, for example, the one trans character in a book, may be removing the only positive representation within the narrative, causing young trans readers to no longer have anyone to relate to on a personal level.

There are also too many situations in which a queer character experiences great tragedy simply because they are queer, as a motivation for a straight character. It is necessary for queer characters to be able to live their truth without the threat of being killed off for yet another straight hero, in order to let young queer readers know that they can be happy. ‘Annie on my mind’, written in 1982, was the first YA book to give queer characters a happy ending, and happily there have been many more to since.

Gender representation

Another really interesting aspect of queer representation in the YA genre is the way in which traditionally male and female queer people and their struggles have been presented. Historically, cis queer men have been more likely than cis queer women to be the victims of violence and persecution in relation to their sexuality- longstanding research has shown that, even nowadays, there appears on the surface to be more societal tolerance for cis queer women. This is demonstrated through the fact that female homosexuality was never outlawed in Britain, and also reflected in YA literature- violence is far more likely to happen to a male queer character than a female queer character. This may be because gay men have traditionally been viewed as feminine. Toxic masculinity demands that men view femininity as an inherently bad thing in society, so, throughout history, people have felt threatened by male members of the LGBTQ+ community, as they disrupt the social order, and have also looked down upon them for their association with femininity.

The harassment that queer women face in society, though just as ugly, is very different. They are not viewed as a threat- they have a history of being erased and sexually fetishized. Queer girls in YA novels are less likely to be single than queer boys- Christine Jenkins attributes this to “the fact that a story featuring queer girls is more likely to be a romance”. This sexualisation of the identity of a queer woman has historically been encouraged by some pieces of queer literature, particularly those pieces written by straight men. This is incredibly damaging, as it contributes to an inaccurate image of gay relationships in the minds of some men in which queer women exist for their entertainment and pleasure, causing them to sometimes draw the conclusion that women loving women could not exist– historically, and now, queer women are not taken seriously. It all stems from the idea that queer women must still exist, in some capacity, for the sake of men. The root of this issue is then, therefore, the patriarchal structure of society as we know it.

Sexualisation of queer men, however, is also rampant in YA literature. In fact, many of the most popular gay YA novels are written by straight women, such as Simon Vs the Homo Sapiens Agenda by Becky Albertelli, Carry on by Rainbow Rowell or the Song of Achilles by Madeleine Miller. The demographic written about the most in queer YA is gay cis white men. Cis boys outnumbered cis girls in LGBTQ+ YA novels 4 to 1 in 1992, and still do around 2 to 1 today.

Conclusion

The good news is, although there’s still a long way to go, good queer representation in YA literature has improved greatly. More novels are being released which do not simply focus on the shame and struggles people experience for being LGBTQ+, usually in the typical coming out narrative. There is a lot of complexity available in these stories, but the sheer number of them compared to other books does create the need for more stories where the queer character has trials and tribulations unrelated to their sexuality. This need is beginning to be met more and more often. I’m so happy that we have worked our way through decades of book banning and ignorance to a moment in time in which the young adult genre finally seems to be beginning to reflect the world that young people are living in today.

By Molly Bell